Brand Strategy for Professional Services: The Operating System of Strategic Identity

Executive Preface: The Initialization of Value

In computer science, 'Hello World' is the standard test phrase, but it signifies something critical: the moment code becomes a functioning program. It proves the system is live. For a professional services firm, this report serves a parallel function. It is the initialization sequence for a brand strategy—the source code that will govern how the entity processes value, signals identity, and navigates the complex, often irrational landscape of the digital marketplace.

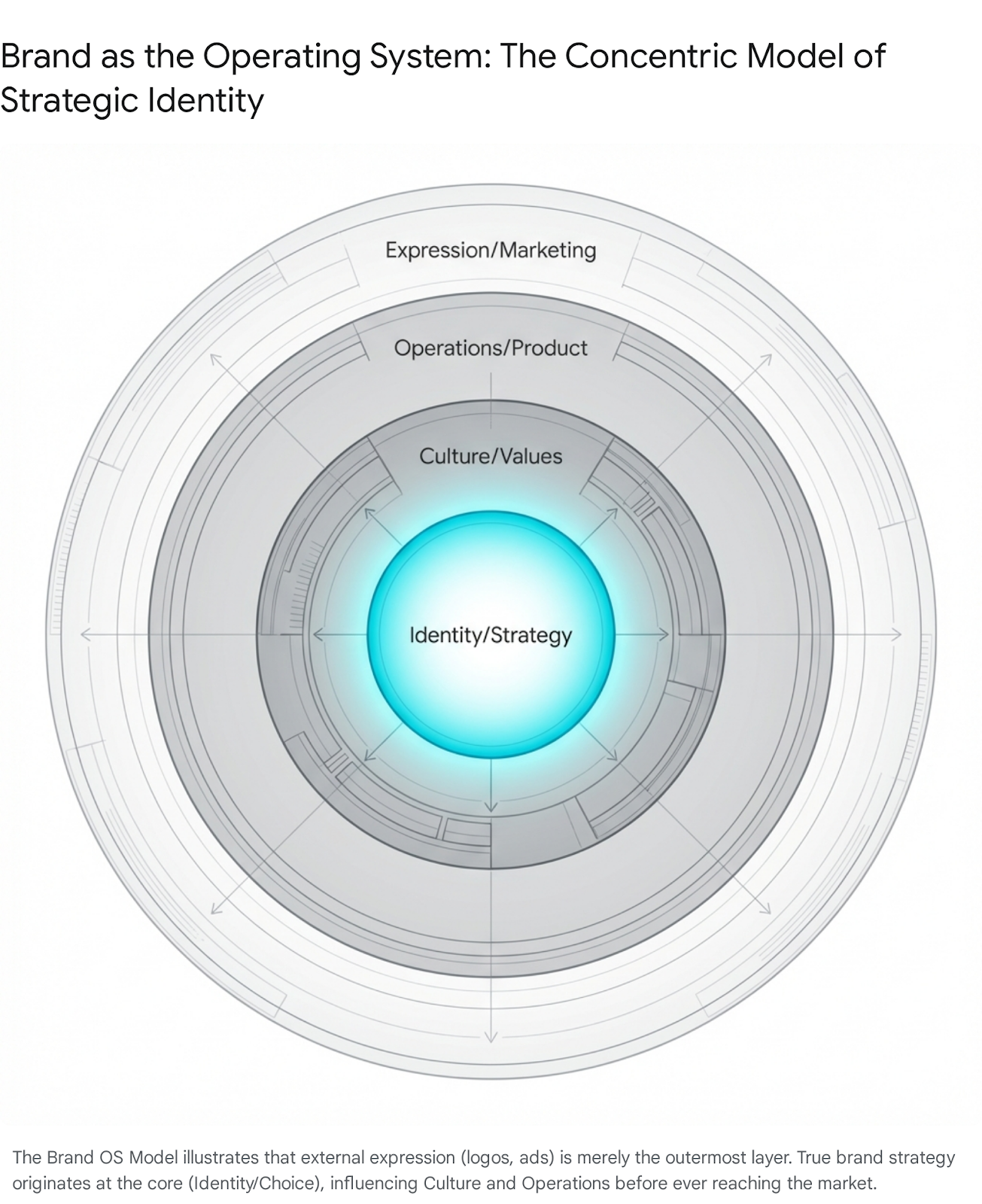

Contemporary business literature is saturated with the notion that "brand" is an aesthetic veneer—a cosmetic application of logos, palettes, and typography designed to make commerce palatable. Treating brand as decoration is a fundamental strategic error. A brand is not what a business looks like; it is what a business is. Brand is simply organizational character made visible. It aligns what you say externally with how you operate internally, acting as a check against bad strategic choices. As the strategist Roger Martin has rigorously argued, strategy is identity. The choices an organization makes about where to play and how to win are fundamentally expressions of who it is.

This comprehensive report, spanning the psychological foundations of choice, the fierce academic debates of marketing science, and the nuanced cultural signaling of technology stacks, provides an exhaustive roadmap for the modern professional service. This report challenges the idea of the 'rational' B2B buyer, examines the mechanics of growth through the lens of modern marketing science, and argues that in a noisy digital market, having a distinct point of view is the only safety.

Part I: The Cognitive Architecture of Value

Building an enduring brand strategy requires looking past market trends to the one variable that rarely changes: human psychology. Markets are not composed of spreadsheets or algorithms; they are composed of biological entities driven by ancient, subconscious imperatives. The act of choosing a brand—whether a piece of enterprise software or a consumer device—is rarely a purely utilitarian calculation of features and price. It is, fundamentally, an act of identity construction.

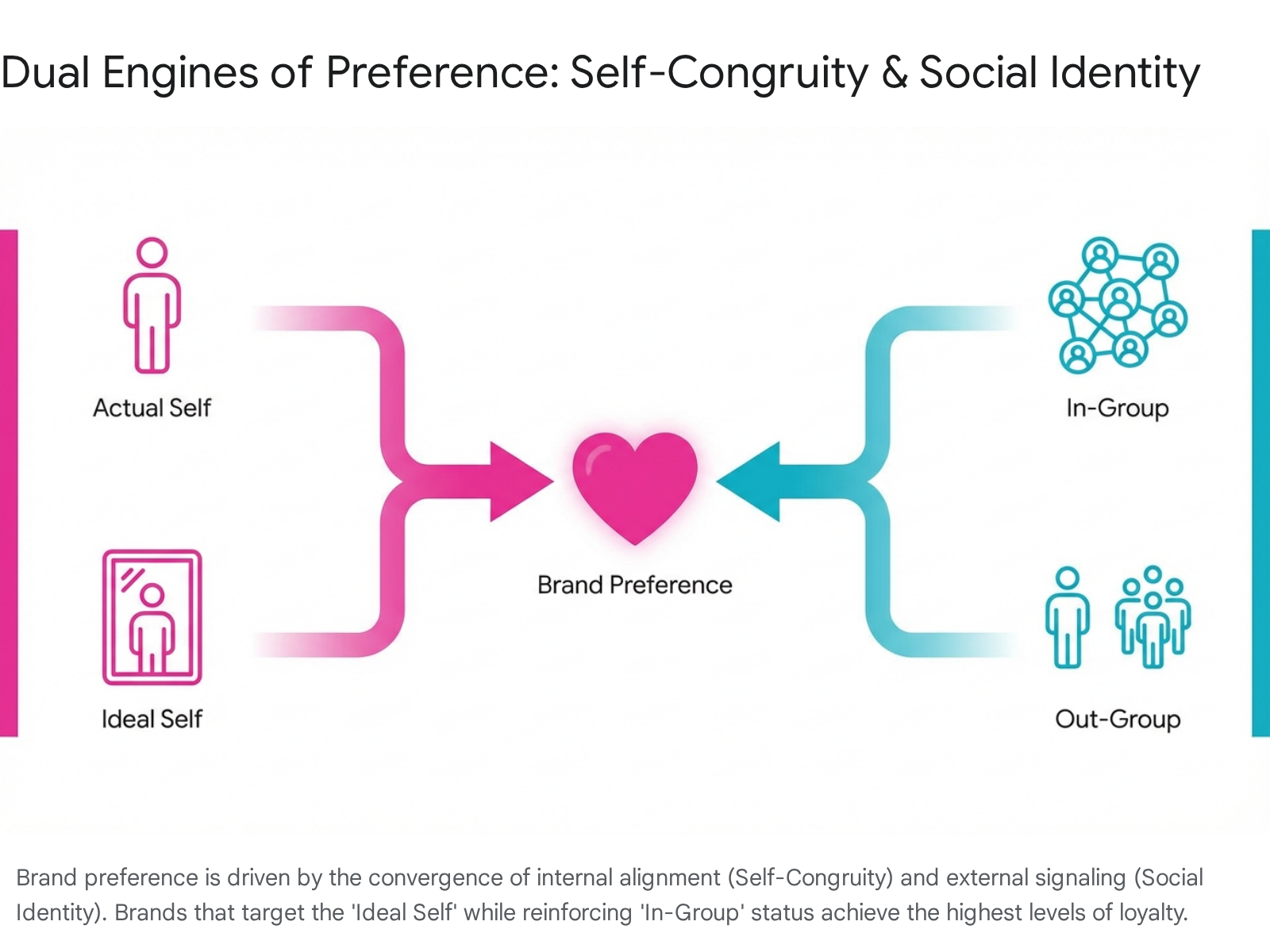

We navigate the marketplace using two primary psychological frameworks: Self-Congruity Theory, which governs our internal sense of self, and Social Identity Theory, which governs our external sense of belonging. Understanding these mechanisms is the prerequisite for moving a brand from a commodity to a necessity.

1.1 The Mirror in the Marketplace: Self-Congruity Theory

Self-Congruity Theory provides the foundational insight that consumers act as curators of their own identity. The theory posits that individuals prefer products, brands, and advertisements that embody characteristics consistent with their self-concepts. When a consumer interacts with a brand, they are engaging in a subconscious comparison process, asking a pivotal question: "Is this brand like me?"

The Multi-Dimensional Self

This mirroring effect is not monolithic; it operates across multiple dimensions of the self-concept. Research identifies distinct layers of congruity:

- The Actual Self: This is the consumer’s perception of who they are in reality. Brands that align with the actual self provide a sense of comfort, validation, and stability. They confirm the consumer’s existing worldview.

- The Ideal Self: This is the aspirational vision of who the consumer wishes to become. This is the most potent lever for brand growth. A brand that aligns with the ideal self becomes a totem of transformation. When a disorganized entrepreneur purchases a complex project management tool, they are not just buying software; they are purchasing the identity of an "organized, efficient executive." The product bridges the gap between their current reality and their aspiration.

- The Social Self: This reflects how the consumer believes they are perceived by others. Brands here act as signals to the external world, helping the user manage their public reputation.

Empirical studies utilizing survey methodologies to evaluate participants' self-concepts against their brand preferences have consistently validated this theory. Consumers display a marked, statistically significant preference for brands that are consonant with their self-concept. Interestingly, this drive for congruity appears to be a universal human trait. Research examining minority versus non-minority participants found no significant differences in the influence of self-image congruity on brand preference. Regardless of demographic background, the human need for psychological consistency drives consumption.

The Well-Being Connection

The implications of self-congruity extend beyond mere preference to actual consumer well-being. Analyses of digital footprints, including datasets of over one million bank transactions, have revealed that spending in a way that is congruent with one’s personality is linked to greater happiness. This suggests that effective brand strategy is not manipulative; rather, it facilitates a form of self-actualization.By clearly articulating its personality, a firm does not just attract clients; it helps those clients feel more aligned with their own professional identities.

However, the execution of this strategy requires precision. While consumers prefer brands with personalities consistent with their own, the "invariance" of self-concept across situations can complicate these findings. A person may view themselves as frugal in their personal life (preferring generic brands) but innovative in their professional life (demanding cutting-edge tech). A B2B brand strategy must therefore target the specific professional self-concept of the buyer, which may differ from their private self.

1.2 The Tribe and the Other: Social Identity Theory

While Self-Congruity deals with the internal mirror, Social Identity Theory addresses the external window—how we define ourselves through group membership. Humans are fundamentally tribal creatures, biologically wired to classify the world into "in-groups" (us) and "out-groups" (them).

Social Identity Theory predicts that consumers will prefer brands that represent the norms, values, and status of their in-group. Consumption becomes a communicative act. By displaying a specific brand logo, a consumer signals their allegiance to a specific social category.

The Mechanics of In-Group Signaling

This tribal signaling is often more powerful than objective product quality. The desire to belong often overpowers the desire for optimization. As the author James Clear has astutely noted, "People would rather be wrong with the crowd than right and by themselves". The social friction of non-conformity is a powerful deterrent to switching brands. Even if a competitor offers a marginally superior feature set, the risk of social isolation—of stepping outside the "norms of the group"—keeps the user loyal to the tribe.

In the context of professional services, this means that establishing the brand as a 'badge' for a specific type of forward-thinking, digital-native client is crucial. Once a brand achieves "in-group" status within a specific demographic (e.g., the preferred agency for SaaS startups), the pressure to comply with that norm drives adoption through peer influence. The brand becomes a shibboleth—a password that grants entry to the club.

Research also highlights gender differences in this domain. While self-image congruity shows little variance by gender, Social Identity does. Studies have found that males may account for more of the relationship between social identity and brand preference than females. This suggests that in male-dominated industries (often the case in legacy IT or industrial B2B sectors), the tribal signaling of a brand—its ability to confer status and group membership—may be an even more critical lever of influence.

1.3 Case Study: The Weaponization of Identity in "Get a Mac"

To understand the practical application of these theories, we must examine the most effective identity campaign in the history of personal computing: Apple’s "Get a Mac" initiative, which ran from 2006 to 2009. This campaign provides a masterclass in how to weaponize Self-Congruity and Social Identity theories to dismantle a competitor.

The campaign did not focus on clock speeds, hard drive capacity, or technical specifications. Instead, it personified the platforms. "Mac" (played by Justin Long) was young, casual, creative, and empathetic—the embodiment of the "Ideal Self" for the creative class. "PC" (played by John Hodgman) was depicted as older, corporate, rigid, and prone to illness—a representation of the stuffy, inefficient "Out-Group".

Constructing the Other

The genius of the campaign lay in its ruthless definition of the "PC" tribe. By portraying the PC as wearing "drab, ill-fitting suits" and exhibiting traits of uncertainty and discomfort , Apple created a powerful negative social identity. No consumer wants to see themselves as the "PC" character. Even if a user was currently a Windows user (their "Actual Self"), the campaign forced them to aspire to the "Mac" identity (their "Ideal Self").

Furthermore, the campaign operated on a subtle socioeconomic level. While Mac and PC were visually distinguished by style, they also represented different class positions. Academic analysis of the campaign suggests that the Mac lifestyle represented the "self-actualized modern individual," reinforcing the ideology that consumption leads to class ascension. Apple effectively obscured issues of class by framing the purchase of a Mac not as a luxury expenditure, but as a necessary step in self-actualization.

Measuring the Impact

The success of such campaigns is not merely anecdotal. Researchers from North Carolina State University have developed systems for measuring "Brand Personality Appeal" (BPA), breaking it down into three components:

- Favorability: How positively the personality is viewed.

- Originality: How distinct the personality is from the category.

- Clarity: How clearly the personality is perceived.

Apple’s campaign excelled in all three. The clarity of the "Mac" vs. "PC" dichotomy left no room for ambiguity. The originality of using human actors to represent hardware was high. And the favorability was engineered by making the Mac character "cool, yet still personable and relatable". This underscores the need for clarity. A brand personality that is "kind of techy but also kind of traditional" fails the clarity test. To win, one must be as distinct as the Mac character standing against the white void.

Part II: The Mechanics of Growth — The Academic Wars

In the realm of academic marketing theory, a fierce debate rages over the fundamental mechanics of brand growth. This is not an abstract discussion; the side of the debate a firm chooses to align with will determine its marketing budget, its messaging strategy, and its operational priorities. On one side stands the traditional view of Differentiation; on the other, the empiricist school of Distinctiveness.

2.1 The Byron Sharp Doctrine: The Primacy of Distinctiveness

The empiricist school, led by Professor Byron Sharp and the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, challenges the sacred cows of traditional marketing. In his seminal work How Brands Grow, Sharp argues that the traditional obsession with "differentiation" (having a unique, meaningful positioning) is largely a myth.

The Myth of Differentiation

Sharp’s research, based on decades of purchasing data, suggests that consumers rarely perceive brands as having deep, meaningful differences. Competitors in a category usually sell to the same types of customers; the user base is rarely segmented by personality or unique needs as much as marketers believe. The "Law of Buyer Moderation" suggests that over time, buying behavior regresses to the mean, and the distinct "personas" marketers target often dissolve into a generic mass of category buyers.

Therefore, focusing on a Unique Selling Proposition (USP) is often a wasted effort. As one summary of the doctrine puts it: "Rather than striving for meaningful, perceived differentiation, marketers should seek meaningless distinctiveness. Branding lasts, differentiation doesn't".

The Laws of Growth

Sharp posits that brand growth is driven not by loyalty, but by Penetration. To grow, a brand must acquire more "light buyers"—people who buy the category infrequently—rather than trying to get "heavy buyers" to buy more. This is governed by two key concepts:

- Mental Availability (Brand Salience): The brand must come to mind easily in a buying situation. This is achieved through "Distinctive Brand Assets" (DBAs)—sensory cues like colors, logos, and jingles that trigger recognition.

- Physical Availability: The product must be easy to buy and access.

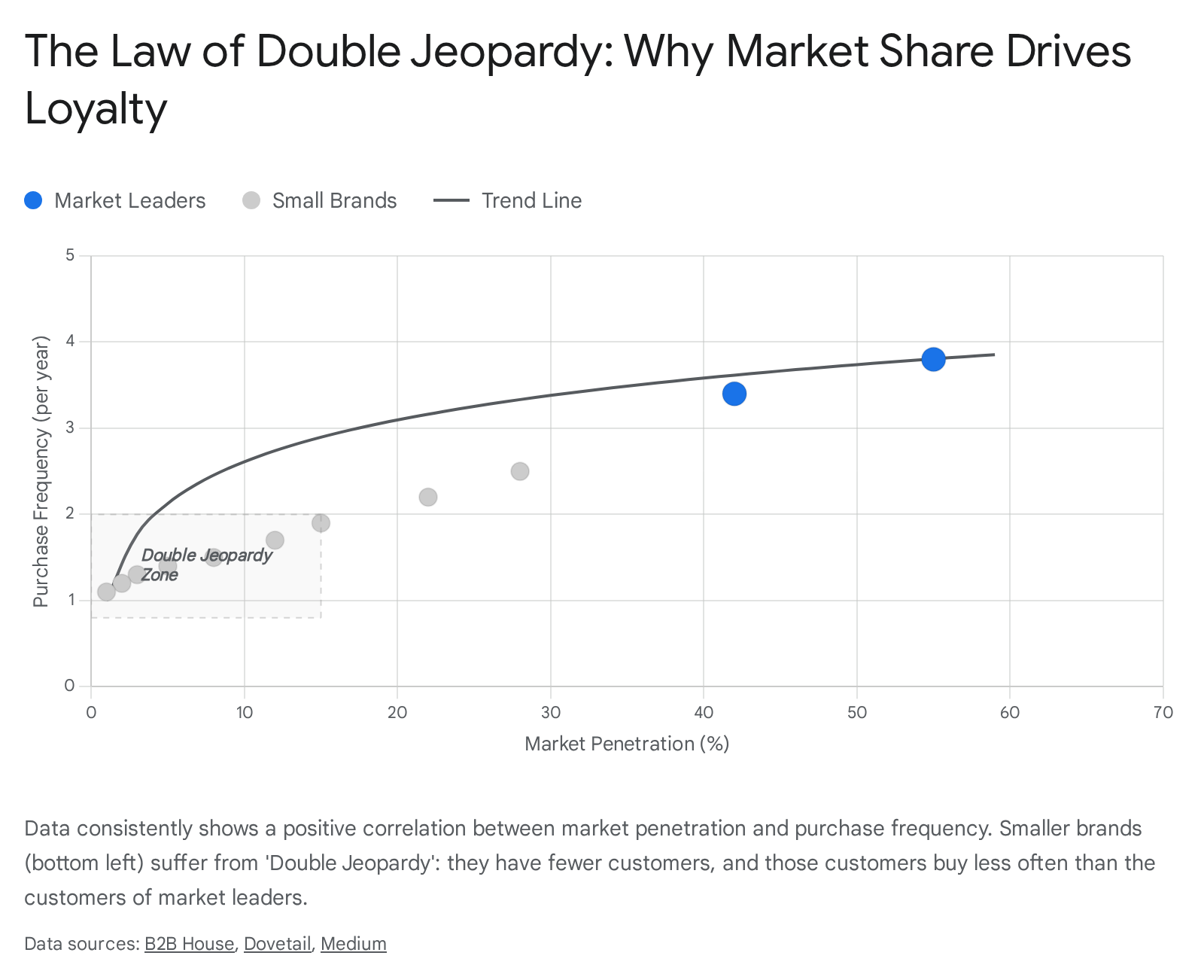

The most critical statistical reality Sharp uncovers is the Law of Double Jeopardy. This law states that smaller brands suffer from a dual disadvantage: they have fewer customers (lower penetration), and those customers are slightly less loyal (lower frequency) than the customers of larger brands. The "niche brand with a small but fiercely loyal following" is a statistical anomaly. To grow a service brand, the goal must be broad reach and mental availability, not just deep loyalty among a tiny cult.

2.2 The Mark Ritson Counter-Argument: The "Both/And" Synthesis

While Sharp’s empiricism provides a necessary corrective to the "fluff" of traditional branding, critics—most notably marketing professor and columnist Mark Ritson—argue that the pendulum has swung too far toward "meaningless distinctiveness."

Ritson contends that while distinctiveness (looking like you) gets you noticed, Differentiation (being different) is what justifies a premium price and drives choice once you are noticed. "Differentiation is a major justifier of premium pricing," Ritson notes. If a brand is merely distinctive but functionally identical to a cheaper competitor, it risks becoming a commodity.

The Commodity Trap

This is particularly dangerous in B2B services. If an agency is merely 'recognizable' but offers no perceived difference in methodology or outcome, it will be forced to compete on price—a race to the bottom. Ritson argues that "relative differentiation" is real. Customers may not perceive a brand as unique in the universe, but they absolutely perceive relative differences between two options in a consideration set. Volvo is safer than Ferrari; Ferrari is faster than Volvo. These are meaningful differentiations.

Ritson’s advice is to "be greedy and have both". Use distinctiveness to trigger memory (the Sharp approach), and use differentiation to give the customer a reason to choose you over the alternative (the Porter approach).

2.3 Synthesis: The Strategy for the Modern Service Firm

For a modern business entity, the synthesis of these views offers the most robust path forward. We must reject the false dichotomy.

- Distinctiveness First (The Hook): You cannot be bought if you are not seen. Establish "Distinctive Brand Assets" (DBAs) immediately. This includes a consistent visual identity (color, logo, shape) that is applied ruthlessly across all touchpoints. This builds the Mental Availability required to even enter the consideration set.

- Differentiation Second (The Closer): Once attention is captured, you must offer a meaningful reason for preference. In the digital space, where features are easily copied, this differentiation often shifts from "what the software does" to "how the company behaves."

- Avoid the Commodity Trap: As Bain & Company’s research highlights, as B2B offerings become commoditized, the subjective and personal concerns of the buyer become more important, not less. The differentiator for a boutique firm will likely be found not in the code it writes, but in the anxiety it reduces and the trust it builds.

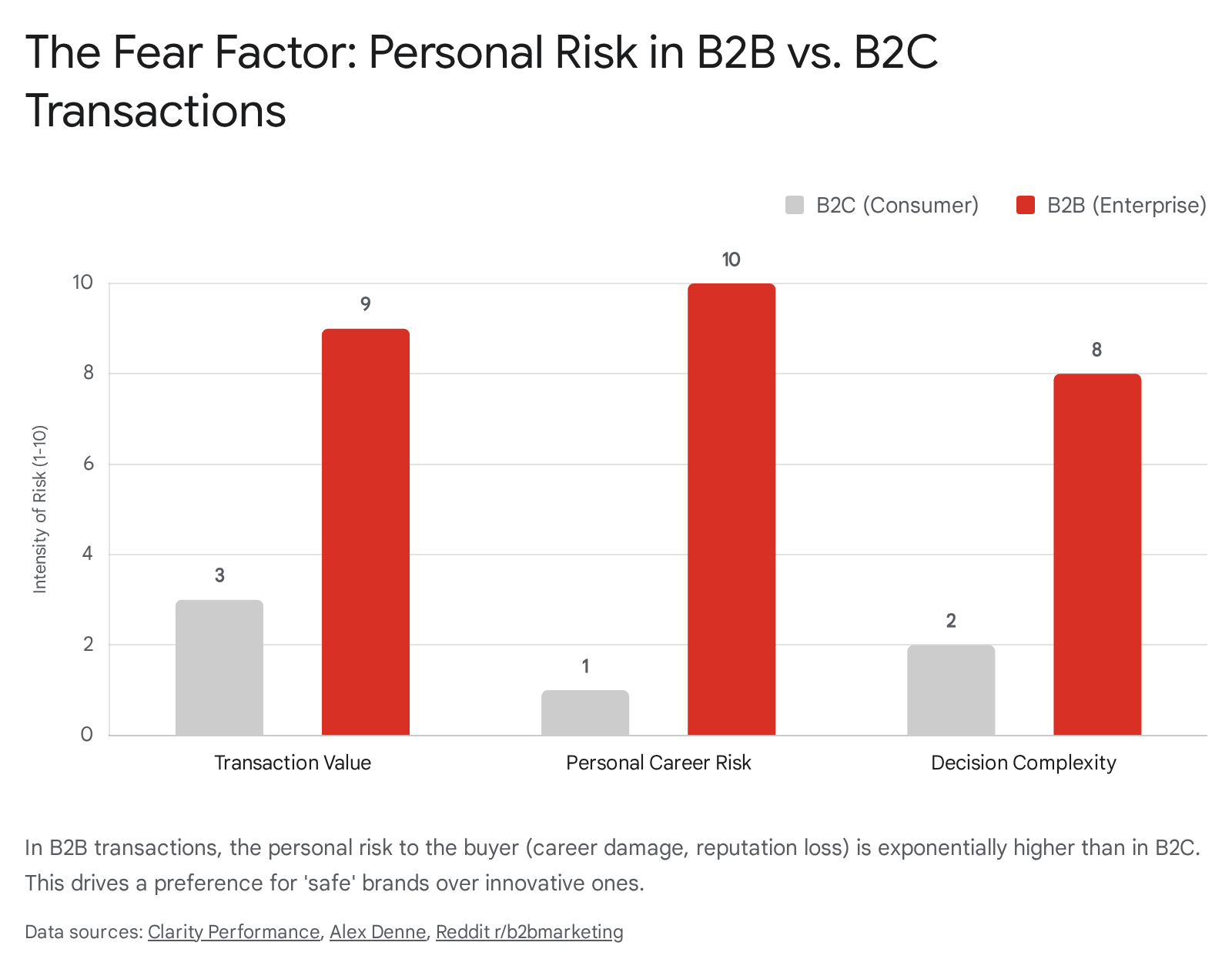

Part III: The Emotional Boardroom — The Psychology of B2B

There is a persistent myth that B2B commerce is a sanctuary of pure logic. In this imaginary world, buying committees sit around mahogany tables, creating weighted spreadsheets of feature sets, and dispassionately selecting the vendor with the highest ROI. This view is not only false; it is dangerous for any brand strategy. The reality is that B2B buyers are biological entities, subject to the same cognitive biases, fears, and emotional needs as any consumer. In fact, the emotional stakes in B2B are often higher, not lower, than in B2C.

3.1 The High Stakes of Fear and Risk Aversion

In a B2C transaction—say, buying a candy bar—the risk of a bad decision is negligible. If the candy bar is subpar, the consumer loses two dollars and experiences a moment of disappointment. In B2B, a bad decision can cost a buyer their reputation, their budget, or even their job.

This creates a psychological environment dominated by Risk Aversion. The enduring adage "Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM" speaks to this fundamental truth. B2B buyers are often motivated less by the desire to gain a "win" and more by the intense fear of a "loss." They are looking for the "least bad option" that protects them from negative repercussions.

The Psychology of "Loss Aversion"

This behavior is rooted in the psychological principle of Loss Aversion—the idea that the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining. In B2B, this manifests as a strong bias toward the status quo or the market leader. When a buyer chooses a giant like Salesforce over a cheaper, potentially more innovative startup, they are buying safety. They are outsourcing the risk to the brand's reputation.

For the emerging challenger brand, this presents a challenge: How does a new entity compete with established giants? The answer lies in branding as a risk-mitigation tool. A strong brand signals stability, reliability, and social proof. It serves as an emotional insurance policy for the buyer.

3.2 The Elements of Value Pyramid

To understand what B2B buyers truly value beyond price and specs, we turn to the rigorous research conducted by Bain & Company. They identified 40 distinct "Elements of Value" for B2B buyers, organized into a pyramid structure similar to Maslow’s hierarchy.

- Tier 1: Table Stakes (Base): Regulatory compliance, ethical standards, pricing. These are the minimum requirements to enter the conversation.

- Tier 2: Functional Value: Performance, scalability, cost reduction. This is where most B2B marketing lives, focusing on "better, faster, cheaper."

- Tier 3: Ease of Doing Business: Productivity, operational simplicity, fit.

- Tier 4: Individual Value: Reduced anxiety, fun, design, aesthetics, growth.

- Tier 5: Inspirational Value (Top): Vision, hope, social responsibility.

Crucially, Bain found that as B2B offerings become commoditized, the subjective and personal concerns at the top of the pyramid (Tier 4 and 5) become more important, not less. When two software platforms have identical feature sets (Functional Value), the decision is made based on which one "reduces anxiety" or "enhances the buyer's reputation" (Individual Value). This aligns with the "Individual" tier's focus on personal needs.

For the service provider, this implies a messaging strategy that transcends technical specifications. The brand must articulate how it makes the buyer’s life easier, how it makes them look good to their superiors, and how it reduces the gnawing anxiety of a complex implementation.

3.3 The Dominance of Emotion

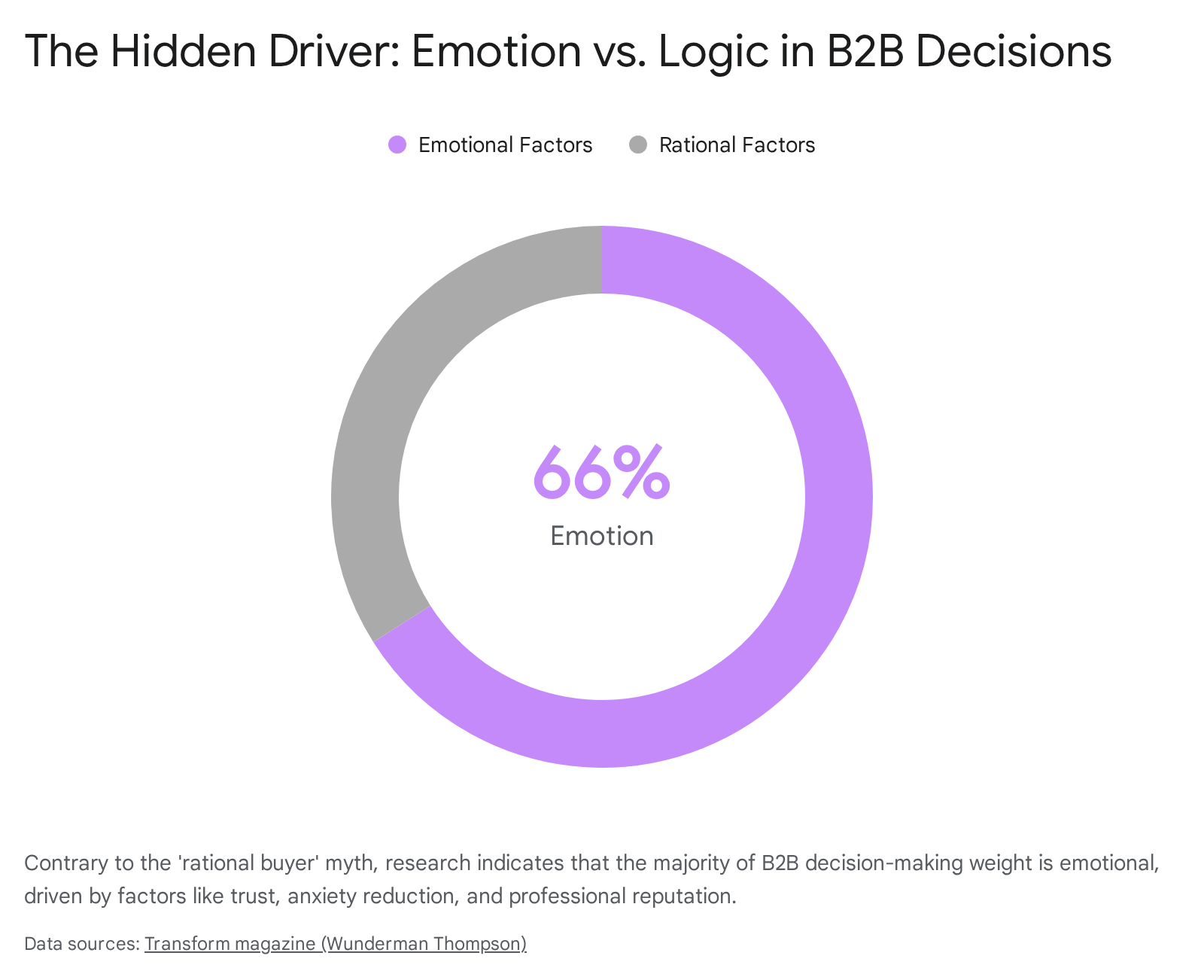

Recent data reinforces this emotional dominance with startling clarity. The LinkedIn B2B Institute found that inspiring emotion in B2B marketing is seven times more effective than focusing solely on rational benefits. Research by Wunderman Thompson suggests that B2B buying decisions are 66% based on emotion and only 34% based on rational factors.

Why is this the case? Because the B2B buying journey is no longer linear. A Forrester study describes the journey as "zig-zagging" and "messy," involving multiple stakeholders with conflicting agendas. In this chaos, an emotional connection—trust, confidence, and shared vision—acts as the glue that holds a deal together. A brand that feels "right" can bypass weeks of logical scrutiny.

The "rep-free" trend further complicates this. Gartner research shows that 61% of B2B buyers prefer a rep-free buying experience. They do not want to talk to a salesperson until they have already made up their mind. This means the brand must do the heavy lifting of building emotional trust without a human ever being involved. The digital experience must communicate empathy, understanding, and safety autonomously.

Part IV: Digital Body Language — The Interface of Trust

In the absence of a physical handshake, a company’s digital presence becomes its body language. For a digital-first entity, the website is not a brochure; it is the built environment in which the brand lives. It is the showroom, the boardroom, and the contract all in one. Research from the Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab provides a rigorous framework for understanding how credibility is constructed in this environment.

4.1 The Aesthetic-Usability Effect and the 50ms Rule

The Stanford Guidelines for Web Credibility reveal a startling truth: people judge a book by its cover, and they judge a business by its pixels. One of their most consistent findings is that "people tend to evaluate the credibility of communication primarily by the communicator's expertise," but this expertise is often inferred almost exclusively from visual design.

This phenomenon is known as the Aesthetic-Usability Effect. Users perceive more aesthetically pleasing designs as being more usable and, critically, more credible. A landmark study demonstrated that first impressions of a website are formed within 50 milliseconds (0.05 seconds). This is far too fast for any cognitive analysis of the text or value proposition. This "gut feeling" is an autonomic response driven entirely by visual appeal.

The hierarchy of digital trust is foundational. Research indicates that 94% of users cite design as the primary reason for mistrusting a website. If the design looks amateurish, the user’s subconscious immediately tags the information as untrustworthy. Only after this visual threshold is crossed do users evaluate content authority or service utility. As the Stanford guidelines note, "Typographical errors and broken links hurt a site's credibility more than most people imagine". In the B2B context, where the buyer is looking for the "safe" option (as discussed in Part III), a broken layout or dated aesthetic is a red flag that signals operational incompetence.

4.2 Design as a Trust Signal in the Rep-Free Journey

We established that B2B buyers are increasingly preferring self-service journeys. Statistics show that 75% of consumers admit to judging a company's credibility based on their website design. When a buyer is conducting rep-free research, the website is the only proxy for the company's competence.

For the modern agency, this means that 'brand strategy' is inseparable from 'design strategy.' High-quality, custom imagery, intuitive navigation, and a modern "tech stack" aesthetic are not artistic indulgences; they are commercial necessities. They are the digital suit and tie that allows the buyer to feel safe signing the contract.

Specific trust signals identified by Stanford include:

- Physical Address: Listing a physical address boosts credibility by proving a "real organization" exists behind the site.

- Ease of Use: Sites that are easy to navigate are perceived as more trustworthy. Complexity is often confused with obfuscation.

- Restraint: The use of restraint in promotional content (e.g., avoiding pop-ups) signals confidence and respect for the user.

Part V: The Culture Stack — Tools as Totems

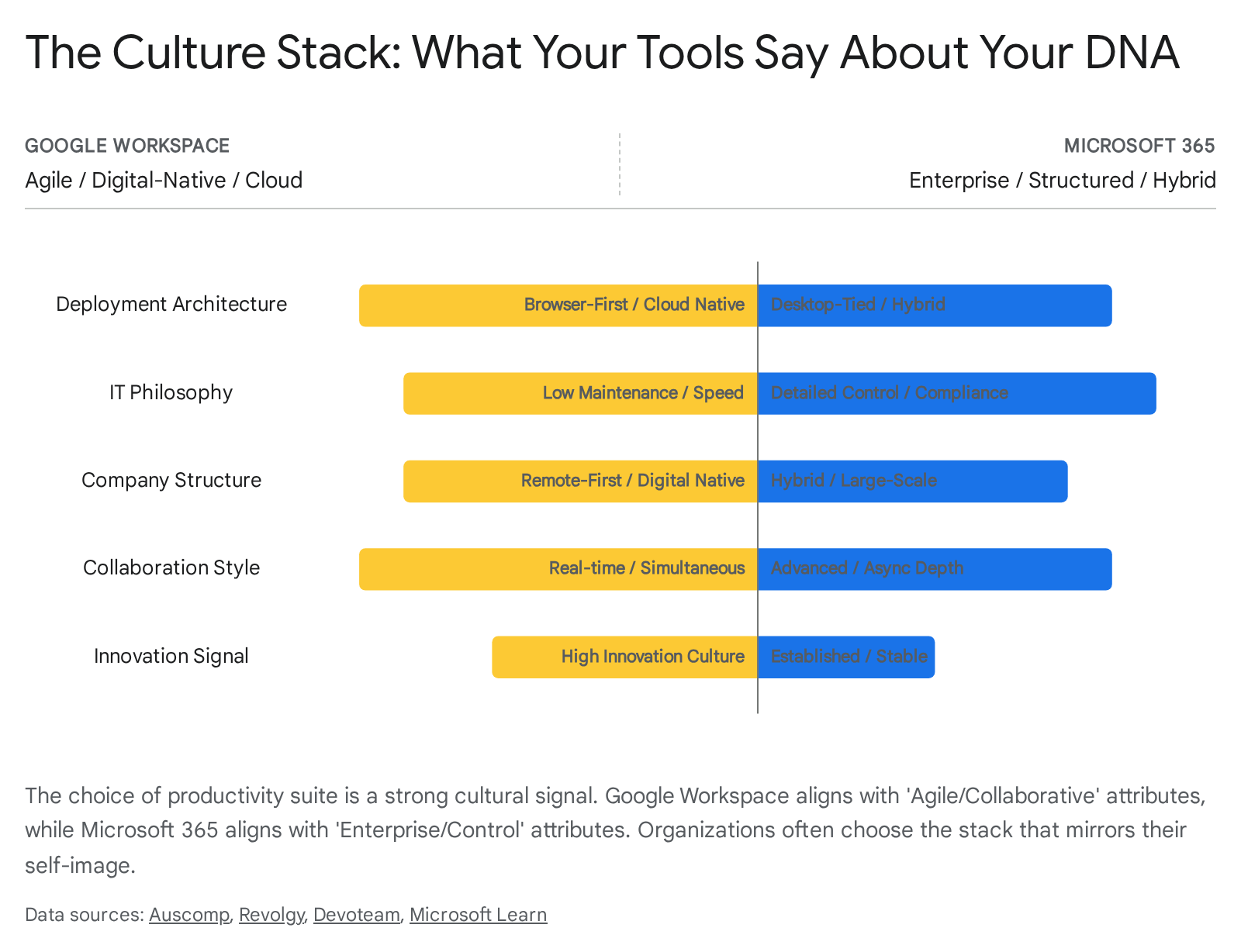

Brand strategy extends beyond the public-facing website and into the very tools a company uses. In the digital economy, the "tech stack" is a cultural signal. It tells employees, partners, and clients what kind of organization you are. This concept, known as the "Culture Stack" , posits that the software a company chooses is a reflection of its organizational DNA.

5.1 The Great Divergence: Google vs. Microsoft

A fascinating cultural divergence has emerged in the corporate world between the "Microsoft Shop" and the "Google Shop." This is not merely a matter of IT preference; it is a signal of values, hierarchy, and operational philosophy.

- The Microsoft 365 Shop (The Enterprise Suit): This stack signals an enterprise mindset. It prioritizes control, compliance, legacy compatibility, and hierarchy. It is the "suit" of the digital world. The choice of Outlook, Excel, and Teams often correlates with larger, more structured, and risk-averse organizations. It signals "we are serious, we are secure, and we speak the language of the Fortune 500."

- The Google Workspace Shop (The Agile Hoodie): This stack signals a startup or agile mindset. It prioritizes real-time collaboration, speed, cloud-native workflows, and organizational flatness. It is the "hoodie" of the digital world. The choice of Docs, Gmail, and Meet correlates with digital-native, younger, and more innovative teams. It signals "we are fast, we are collaborative, and we are modern."

One commentator aptly summarized the cultural difference: "Microsoft is like Star Wars, Google is like Star Trek." Both are powerful, but they represent fundamentally different visions of the future.

For a new market entrant, this choice is a strategic branding decision. Using Google Workspace signals to prospective talent and clients that the entity is modern and collaborative. However, if the target clients are primarily legacy enterprises, possessing Microsoft Teams capability (or a dual-stack approach) might be a necessary signal of "enterprise readiness"—a form of social identity alignment with the client's in-group.

5.2 The Tech Stack as Employer Brand

The culture stack also exerts a profound influence on talent acquisition and retention. Younger generations (Millennials and Gen Z) often show a marked preference for the Google ecosystem, viewing it as more user-friendly and innovative. Research shows that 75% of Google Workspace users say their team has become more innovative since adopting the software, compared to lower rates for Microsoft users.

Furthermore, forcing a digital-native employee to use clunky, legacy enterprise tools can actually decrease employee satisfaction. 76% of Workspace users report that the platform improves employee retention, versus 58% for Microsoft. Your internal tools are the daily environment in which your culture is practiced. As one expert notes, "Your culture is the glue that holds [product and engineering] together. You should think about your 'culture stack' just as often as you think about your tech stack".

Part VI: Execution as Strategy — The Decision Filter

Finally, we return to the definition of strategy itself. If brand is identity, then brand strategy is the discipline of making choices that align with that identity. It is not enough to define the brand; one must live it through every operational decision.

6.1 The "Playing to Win" Framework

Roger Martin’s "Playing to Win" framework simplifies strategy into five integrated choices:

- What is our winning aspiration? (The purpose).

- Where will we play? (The market/geography).

- How will we win? (The value proposition).

- What capabilities must we have? (The internal skills).

- What management systems are required? (The metrics and tools).

For a brand, the most critical of these is "How will we win?" This is where the differentiation vs. distinctiveness debate is resolved practically. You win by being distinct enough to be found (Mental Availability) and different enough to be valued (Differentiation).

6.2 The Brand as a Decision Filter

The ultimate utility of a brand strategy is its function as a Decision Filter. It is a tool for saying "no." When a new opportunity arises—a new service line, a potential client, a marketing channel—the leadership must ask: "Does this align with our brand identity?"

If the brand identity of a creative agency is defined as 'Agile, Digital-Native, and Creative,' then taking on a project that requires rigid, waterfall compliance for a bureaucratic government agency might be a strategic error, even if it is profitable. It dilutes the identity. It confuses the market. It introduces "incongruity" into the system.

Successful brands are consistent. They represent their brand in the same way over a long period. A "Brand Filter" helps teams think through how to talk, act, and decide. It turns subjective debates into objective checks against the core truth of the business. As one expert notes, "The most overlooked part of brand identity is not a logo or color. It is the decision filter. A sharp line that tells your team what to say yes to and what to ignore".

6.3 Personal Branding: The Founder's Role

For a boutique entity or consultancy, the corporate brand is often inextricable from the founder's personal brand. Harvard Business School research highlights that personal branding is the intentional, strategic practice of defining and expressing one's value proposition. The goal is to ensure the narrative is Accurate, Coherent, Compelling, and Differentiated.

The founder serves as the primary "Distinctive Brand Asset" in the early stages. The consistency of the founder's voice, their choice of "Culture Stack," and their visible expertise act as the initial seed for the corporate brand's equity.

Conclusion: The Source Code of Strategic Identity

For the ambitious firm, this report is not just an analysis; it is a compilation of source code for the entity's future.

The research is unequivocal:

- Identity is King: You must define who you are so clearly that clients can use you to signal who they are (Self-Congruity).

- Emotion is the Driver: In the B2B space, you are selling anxiety reduction and reputation insurance, not just code or strategy. The "Rational Buyer" is a myth.

- Design is Trust: Your digital surface area must be impeccable to survive the 50-millisecond judgment of the modern buyer. A broken link is a broken promise.

- Tools are Culture: Your internal stack is an external signal. Choose it to match your DNA, and use it to attract the talent that shares your values.

- Strategy is Rejection: Use your brand identity to say "no" to opportunities that dilute your distinctiveness.

"Hello World" is the first step of a program coming to life. It is a humble beginning, but it implies infinite potential. By architecting a brand strategy grounded in these psychological and strategic truths, the organization positions itself not just to exist, but to resonate. To be distinct. To be different. And ultimately, to be chosen.

Works cited

1. The Oxford Handbook of Grand Strategy 9780198840299, 0198840292 - DOKUMEN.PUB, https://dokumen.pub/the-oxford-handbook-of-grand-strategy-9780198840299-0198840292.html

2. Who You Are Affects What You Buy: The Influence of Consumer Identity on Brand Preference, https://eloncdn.blob.core.windows.net/eu3/sites/153/2017/06/01IlawEJFall14.pdf

3. The Role of Self-Congruity in Consumer Preferences: Perspectives from Transaction Records - UCL Discovery, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/10137531/13/Cui%20Ling%20Lay%20PhD%20thesis%20Final%20Version.pdf

4. Who You Are Affects What You Buy: The Influence of Consumer Identity on Brand Preferences - Inquiries Journal, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1035/3/who-you-are-affects-what-you-buy-the-influence-of-consumer-identity-on-brand-preferences

5. The retail brand personality—Behavioral outcomes framework: Applications to identity and social identity theories - Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903170/full

6. Interview with James Clear | Mastering the Art of Showing Up - Pragmatic Thinking, https://pragmaticthinking.com/blog/james-clear-interview/

7. Quote by James Clear: “There is tremendous internal pressure to comply...” - Goodreads, https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/10184421-there-is-tremendous-internal-pressure-to-comply-with-the-norms

8. Get a Mac: Marketing Campaign Review - Anthony Thomas, https://blog.anthonythomas.com/ata-blog/get-a-mac-marketing-campaign-review

9. Better at Life Stuff: Consumption, Identity, and Class in Apple's “Get a Mac” Campaign - digitalmediafys, http://digitalmediafys.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/68477937/Livingstone_R_2011_Mac_Identity_Consuption.pdf

10. 'I'm a Mac' – So What? Study Finds Way To Measure Brand Personality Appeal, https://news.ncsu.edu/2011/04/wms-henard-brandpersonality/

11. How Brands Grow - Book summary and guide - Tamarind's B2B House, https://www.theb2bhouse.com/how-brands-grow-book-summary-and-guide/

12. Summary: How Brands Grow by Byron Sharp | by Emma Sharley - Medium, https://medium.com/@emsharley/summary-how-brands-grow-by-byron-sharp-fc22a1ab436c

13. How Brands Grow | Summary & Notes - Will Patrick, https://www.willpatrick.co.uk/notes/how-brands-grow-byron-sharp

14. How Byron Sharp's "How Brands Grow" Reshaped Market Research - Dovetail, https://dovetail.com/market-research/how-brands-grow-changed-market-research/

15. Differentiation vs distinctiveness | The Drum, https://www.thedrum.com/profile/woven-agency/article/differentiation-vs-distinctiveness

16. 'Don't call it science, call it what it really is: consulting, dogma, ideology': Mark Ritson on why Ehrenberg-Bass has distinctiveness v differentiation wrong – and how brands grow better with both | Mi3, https://www.mi-3.com.au/30-08-2023/dont-call-it-science-call-it-what-it-really-consulting-dogma-ideology-mark-ritson-why

17. The B2B Elements of Value | Bain & Company, https://www.bain.com/insights/the-b2b-elements-of-value-hbr/

18. Power Laws | The Biology of Business - Alex Denne, https://alexdenne.com/books/scale-and-complexity/power-laws/

19. Dear Analyst #95: Nobody ever got fired for choosing Google Sheets • - KeyCuts, https://www.thekeycuts.com/dear-analyst-95-nobody-ever-got-fired-for-choosing-google-sheets/ 20. B2B buyers are loss averse : r/b2bmarketing - Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/b2bmarketing/comments/1iqxtjj/b2b_buyers_are_loss_averse/

21. Bain Pyramid for B2B: Unveiling Client Value and Ensuring Appreciation - Priceva, https://priceva.com/blog/b2b-bain-pyramid

22. Six elements of value that drive strategic B2B relationships | Article - Visma, https://www.visma.com/resources/content/elements-of-value-that-drive-strategic-b2b-relationships

23. B2B Decision making is non-linear, emotional, and messy - Intelligent Marketing, https://intelligentmarketing.co.uk/b2b-decision-making-is-non-linear-emotional-and-messy/

24. Gartner Sales Survey Finds 61% of B2B Buyers Prefer a Rep-Free Buying Experience, https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2025-06-25-gartner-sales-survey-finds-61-percent-of-b2b-buyers-prefer-a-rep-free-buying-experience

25. Analysts say B2B prospects form preferences earlier and avoid sales conversations later, https://www.swordandthescript.com/2025/08/b2b-preferences/

26. Credibility judgments in web page design – a brief review - PMC - NIH, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4863498/

27. 90+ Web Design Statistics for 2025 - Tenet, https://www.wearetenet.com/blog/web-design-statistics

28. The Web Credibility Project: Guidelines - Stanford University, https://credibility.stanford.edu/guidelines/index.html

29. How Much Does B2B Website Design Impact Your Bottom Line? - Creative Click Media, https://creativeclickmedia.com/b2b-website-design-bottom-line/

30. How the 'culture stack' is reshaping art and technology - The World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/07/the-rise-of-the-culture-stack-what-is-it-and-how-is-it-reshaping-art-and-technology/

31. Microsoft 365 vs Google Workspace: Which Work Suite Fits Your Business Best in 2026?, https://auscomp.com/microsoft-365-vs-google-workspace-which-work-suite-fits-your-business-best-in-2026/

32. Google Workspace vs. Microsoft 365: 2026 strategic playbook for enterprises - Revolgy, https://www.revolgy.com/insights/blog/google-workspace-vs-microsoft-365-2026-strategic-playbook-for-enterprises

33. Google Workspace or Microsoft 365 for a growing business? : r/sysadmin - Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/sysadmin/comments/1kbm8rd/google_workspace_or_microsoft_365_for_a_growing/

34. Google Workspace vs Microsoft 365: which one comes out on top? - Devoteam, https://www.devoteam.com/expert-view/google-workspace-vs-microsoft-365-which-one-comes-out-on-top/

35. Cultural Difference Between Google And Microsoft Boils Down To Their Food - Foodbeast, https://www.foodbeast.com/news/ex-google-employee-makes-a-brilliant-observation-about-microsoft-and-googles-meal-plans/

36. Understanding the Preference of Google over Microsoft Among the Younger Generation, https://www.digitalvibes.ai/post/why-the-younger-generation-may-prefer-google-over-microsoft

37. Your “Culture Stack” is more important than your Tech Stack | by Andrew Martinez-Fonts, https://medium.com/@amartinezfonts/your-culture-stack-is-more-important-than-your-tech-stack-f5831f8a1a57

38. Playing to Win! : r/managers - Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/managers/comments/1lsf8kl/playing_to_win/

39. Branding Fundamentals: brand filter | A Brave New, https://www.abravenew.com/blog/branding-fundamentals-brand-filter

40. What's the most overlooked part of brand identity? : r/branding - Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/branding/comments/1ok8z74/whats_the_most_overlooked_part_of_brand_identity/

41. Personal Branding: What It Is and Why It Matters - HBS Online - Harvard Business School, https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/personal-branding-at-work